Planning for panic

When things go wrong, people react badly. They get nervous and start rushing around, trying to do everything at once, achieving all too little. You see this in everyday life, and in the financial markets. You’re seeing it now with the coronavirus – a headline from Reuters last week said “COVID-19 – Business as usual, or panic stations?”

But in the Royal Navy, ‘panic stations’ wasn’t a description of frantic behaviour. It was a command for sailors to move to assigned positions when something was going wrong. ‘Panic stations’ was, in fact, a plan to deal with unexpected events.

This week, we’ve been adding to corporate bonds in our portfolios. Of course, as you’d expect from 7IM, we’re not piling in.

So at 7IM, in the Investment Team, at times like this we move to panic stations – in the original sense. We have a process that is designed to deal with uncertain and fast-moving markets. Part of the process is quantitative, looking at a dashboard of different economic and market indicators. Part of it is qualitative, discussing policy and views rather than hard numbers. And part of the process is ensuring that we are talking to one another, that information and views are shared clearly and honestly.

Relying on this process allows us to move from panic stations into more orderly and considered behaviour – encouraging us to look for the opportunities that big market dislocations tend to throw up.

Corporate credit and high yield bonds

Our portfolios have strategic allocations to corporate bonds, with globally diversified holdings in both investment grade and high yield rated debt. Over the long term, these bonds tend to have higher returns than government bonds, with the extra yield (sometimes called spread) more than compensating for the risk.

The main risk with any corporate bond is that the company defaults, and doesn’t pay the investor back. Credit rating agencies assign ratings to bonds accordingly. A rating of BBB or higher is viewed as good quality with a low chance of default, and is referred to as investment grade. Bonds with lower ratings than BBB are called high yield bonds, because the companies are seen as riskier – they have a greater chance of going bust – so the companies issuing them have to pay a higher yield to investors.

Right now, both investment grade and high yield bonds look very interesting. Over the past decade of low rates, many investors have been drawn in to the corporate bond market, due to the higher yields on offer. But many of these investors haven’t done the work needed to be confident in holding these bonds. When there’s an equity market shock, they overreact and sell anything in their portfolio that isn’t cash or a government backed asset.

The bonds of high quality companies are being sold as if they’re heading for bankruptcy, while lower quality company bonds are being priced as if the bailiffs are knocking on the door. That’s the fear and panic talking.

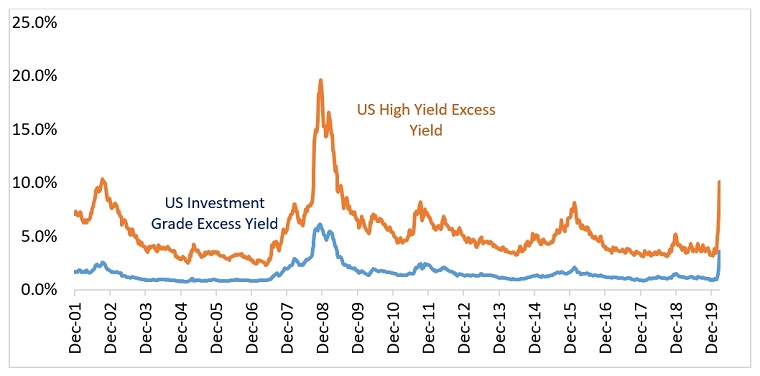

Investment grade corporate bonds usually pay about 1% more a year than government bonds, but currently, they’re offering 3% more. High yield bonds normally offer around 3% over government bonds, but are currently paying nearly 10% more. As the chart below shows, these kind of yields haven’t been seen since the financial crisis in 2008/2009.

Corporate bonds tend to recover more quickly than equity markets following a sell-off. After the financial crisis, it took US equities until 2012 to make back their losses. It only took the high yield bond market until the end of 2009. This makes sense, because companies have to pay their debts before they can reward their shareholders. We believe a similar outcome is likely with the COVID-19 crisis, particularly given the financial support that governments are giving to businesses across the world – guaranteeing their loans, subsidising their businesses and even paying their staff for them.

This week, we’ve been adding to corporate bonds in our portfolios. Of course, as you’d expect from 7IM, we’re not piling in. We’ve moved high yield from an underweight allocation to a small overweight position (a 3% addition for a Balanced portfolio), and also begun taking investment grade back towards neutral from an underweight position (a 4% addition for a Balanced portfolio). The risk of default is low, and we are being paid generously to wait while the rest of the world figures that out.

Source: Refinitiv

We’re excited to announce that 7IM for Private Clients, London, has now merged with, and rebranded to, Amicus Wealth Management.

This marks a vital step forward in our mission to deliver the very best wealth management for our clients.

While our name has changed, our values and commitment remain the same. We’ll continue to provide personal, bespoke financial planning, built around you.

Explore Amicus Wealth Management